Classic value investing, modern value investing, contrarian investing, deep value investing, classic Graham investing… with so many value investing terms batted around it's easy to get lost.

Investors today have a tsunami of investment styles to choose from, not to mention index investing, flipping houses, or starting online businesses. This variety has caused a lot of confusion among the ranks of value investors as new investors try to find their financial footing. Many pick up value investing after discovering Warren Buffett and his (albeit large) cult-like following. Once investors dig a little deeper to figure out how exactly he earned his enormous wealth, they start to learn about Buffett's teacher, Ben Graham and the classic value strategies that Buffett started with.

It's not long before smart value investors begin to probe the depths of deep value and realize that these strategies were responsible for the largest percentage returns of Buffett's investing career. But what exactly is deep value investing and should you use deep value to earn your fortune?

To really do this topic justice, we need to start by contrasting modern value investing with classic value investing because deep value is firmly embedded in the classic value paradigm. So…

Table of Contents

What is the Modern Value Paradigm?

Warren Buffett himself has to be given credit for creating the modern value paradigm, or at least bringing it into focus. Buffett gave birth to modern value investing in his 1993 Berkshire Hathaway letter when he wrote:

"Indeed, many investment professionals see any mixing of the two terms [TBL Note: growth investing versus value investing] as a form of intellectual cross-dressing.

We view that as fuzzy thinking (in which, it must be confessed, I myself engaged some years ago). In our opinion, the two approaches are joined at the hip: Growth is always a component in the calculation of value, constituting a variable whose importance can range from negligible to enormous and whose impact can be negative as well as positive."

With this quote, Buffett forever fused growth investing with value investing in the mind of the investing public. Buffett would later to go on to explain his own style of value investing. In this article, we've dubbed it modern value investing, and it seeks to identify firms that have a significant competitive advantage, or a "moat," so that they can maintain profitable growth.

Firms with moats also have high returns on capital (eg. a high return on equity) which make them superior businesses from a capital allocation standpoint. If you're a business owner and want to put your cash to work in the most productive way possible, you pursue capital projects that can sustain a high return on capital.

Classic value investing, by contrast, doesn't specifically look for great businesses. While it's always nice to buy a great business, the focus of classic Ben Graham value investing is just buying a dollar for much less than its worth. This would include buying firms without moats, also known as commodity businesses, firms suffering terrible business problems, or even firms in bankruptcy.

In fact, while Graham acknowledged the importance of strong competitive advantages, good management, and other intangible advantages, he thought it best to exclude them from analysis. For one, if the business indeed did have great management, that fact would be reflected in the business results themselves - the firm's financial statements. Graham is correct in his assumption, as well. If intangibles, such as brands, have any value then they would allow a business to earn above average profits on tangible assets.

The idea of looking for businesses with strong competitive advantages was redundant for Graham, since he often based his valuation of companies on standard ratios such as price to book value, price to earnings, or price to net current asset value. While there's a bit more to it than this, he could then simply look at the ratios to get a sense of which firms were cheap based on their stated record.

Buffett's shift was to start looking at great businesses and then to pay up for these companies, expecting the profitable business growth to continue. While Buffett was more than happy to pay a PE of 20 or 30x for a great company, for example, Graham would never place that much trust in a company's future growth prospects, explaining that the future is something to be guarded against. Instead, he'd try to buy earnings the company was producing today for much less than they were worth in the market.

Part of Buffett's justification for paying up for great businesses was the idea that an investment is worth the sum total of all future cash inflows and outflows discounted at an appropriate rate. In other words, he shifted to adding up the net present value of all earnings the company would make into the future to arrive at an intrinsic value. This is the practice of counting your chickens before they hatch. Buffett just looks for reliable hens.

Graham's Prelude to Deep Value Investing

Ben Graham would not disagree that the sum total of all future cashflows discounted at an appropriate rate could be a solid assessment of fair value, but his preferred definition varied quite a bit. In the 1951 Edition of Security Analysis, he wrote:

“The newer [TBL note: in 1951] approach to security analysis attempts to value a common stock independently of its market price. If the value found is substantially above or below the current price, the analyst concludes that the issue should be bought or disposed of. This independent value has a variety of names, the most familiar of which is “intrinsic value”.

“A general definition of intrinsic value would be that value which is justified by the facts—e.g. assets, earnings, dividends, definite prospects. In the usual case, the most important single factor determining value is now held to be the indicated average future earning power. Intrinsic value would then be found by first estimating this earning power, and then multiplying that estimate by an appropriate ‘capitalization factor’”.

Graham would also later go on to define intrinsic value as the value that a knowledgable business man would place on the business. This gave Graham an enormous amount of flexibility in his approach. Some later investors, such as Mario Gabelli, would make good use of this definition, assessing the price 3rd parties were paying for entire businesses during a takeover then using this data to assess the intrinsic value of their close competitors.

While future prospects were still important, Graham preferred to assess value based on "the facts" or financial statement figures. Once he decided on which source of value to look at (ie. assets, earnings, dividends, etc) he would then apply an appropriate multiple to arrive at a fair value.

For example, if he predicted that the company in question could earn $5 per share on average, and the market multiple (ie. PE ratio) was 15x, he would value the stock at $75.

$5 average expected earnings

15x market PE ratio

$5 x 15 = $75

While he demanded a minimum 1/3rd discount to fair value, Graham would usually only buy at stock if it was priced well below $75. Here, Graham's 1/3rd discount requirement would mean a stock price of $50 or less.

The PE ratio is only one sort of classic value investing multiple that investors can use when valuing stocks. Investors can also use other basic ratios such as price to book value (shareholder equity) price to tangible book value, price to net current asset value, price to sales, or price to cash flow. In fact, I consider these type of financial ratios to be the defining characteristic of classic Ben Graham value investing.

Deep Value Investing A Subset of Classic Ben Graham Value

Within the deeper classic Ben Graham value paradigm sits a smaller niche philosophy that leverages much of Graham's teachings but produces far higher returns. That niche philosophy is deep value investing.

Graham really had no preference one way or another for good or bad businesses. He was prepared to buy both, if the price was cheap enough. A lot has been made of Buffett's Geico purchase and the enormous amount of money he made on it. Buffett's bet has produced a huge amount of cash for his business empire and is widely regarded as one of the best insurance companies, at least in terms of competitive advantage. Few investors realize that Ben Graham purchased this company long before Buffett was even running his partnership and held it up until he closed his investment company, Graham-Newman.

But there's another feature about this company that made it such an interesting buy. While Graham recognized Gieco's superior business characteristics, Graham purchased it well below his assessment of the company's liquidation value. He explained to Walter Schloss:

"Walter…if this doesn’t work, we can always liquidate it and get our money back."

It's rare for a firm to trade well below its liquidation value but these are exactly the sort of companies that deep value investors look for. Deep value investing is the practice of buying investments for ultra cheap prices relative to conservative valuation frameworks.

When it comes to assessing the fair value of a stock, there's a clear hierarchy of value. Some valuation methods are clearly more conservative than others. Deep value investing either demands an incredibly low price relative to fair value or a discount to an ultra conservative assessment of value. Take a look:

Least Conservative

Value In Growth - This is the value an investor places on larger future earnings when there is no clear indication that the firm possesses a strong competitive advantage. It's also what most of Wall Street looks at (which is partly why most professionals have such terrible track records).

Franchise Value - The value an investor places on the firm's ability to earn much higher than average returns due to possessing some strong competitive advantage. These are the sort of firms that Buffett looks for and are typically assessed using discounted cash flow. Shelby Davis combined franchise value with deep value to produce a fantastic investment record.

Marginally Conservative

Private Market Value - This is the Gabelli method written about above. Firms are valued relative to the average takeover price in the same industry. Industry prices can be inflated or depressed, however.

Earnings Power - This is the firm's ability to produce profit now, today. It is often estimated using past earnings and extrapolating forward. This valuation is often written as a price to earnings (PE) multiple. We're including both earnings and cash flow in this category.

Book Value - This is the company's shareholder equity and reflects the lower of the firm's historic cost of assets, or the market value of those assets. This is a favourite of academics testing value investing and market inefficiency. Walter Schloss was also a fan.

Most Conservative

Dividend Value - The idea here is to look at a firm's dividend and then to apply a market yield to arrive at a fair value measure. Dividends can often continue when earnings drop, so this method is more conservative than earnings power value. With all of these sources of value listed here, investors usually make other adjustments.

Tangible Book Value - An off shoot of book value, tangible book value excludes intangible assets and goodwill.

Negative Enterprise Value - Enterprise value is market cap, plus total debt, minus cash. If there's more cash then the value of the company's debt and market cap, the enterprise value is negative. You're essentially being paid to buy a stock.

Net Current Asset Value - This is an off-shoot of tangible book value, but investors exclude long term assets from the calculation to arrive at a rough assessment of the firm's liquidation value. We suspect that Gieco was trading for less than its net current asset value.

Net Net Working Capital - This is a more conservative approach to net current asset value. Current asset accounts are discounted by varying amounts to arrive at an ultra conservative assessment of a firm's liquidation value. Buffett used this strategy and bought net current asset value stocks to earn the highest percentage returns of his life.

While deep value investing focuses on both the marginally conservative and most conservative categories, it concentrates heavily on the most conservative valuation methods. In other words, every valuation method in the most conservative section can be considered deep value; but, for marginally conservative sources of value to be considered deep value, stocks must be purchased at small fractions of their assessed intrinsic value.

Comparing two investments, a stock priced at a 1/3rd discount to net current asset value would be considered deep value but a stock trading at a 1/3rd discount to its earnings power wouldn't. For the earnings power company to be considered a deep value investment, it would have to be priced at an ultra cheap multiple to its average expected earnings - perhaps at a 60% discount to fair value.

Deep Value Investing Produces Outstanding Returns

If you're new to value investing and you want a comparatively easy approach that produces high returns, deep value investing is your ticket. Don't get me wrong, successful investing is challenging and takes time to do well. This is why I quit my job to focus on investing full time.

When you combine deep value investing with mechanical value investing, you can achieve both safety of principle and a great chance at a great average annual return. We've strived to live up to this Ben Graham principle to build a Graham-styled investment letter the Dean of Wall Street would be proud of.

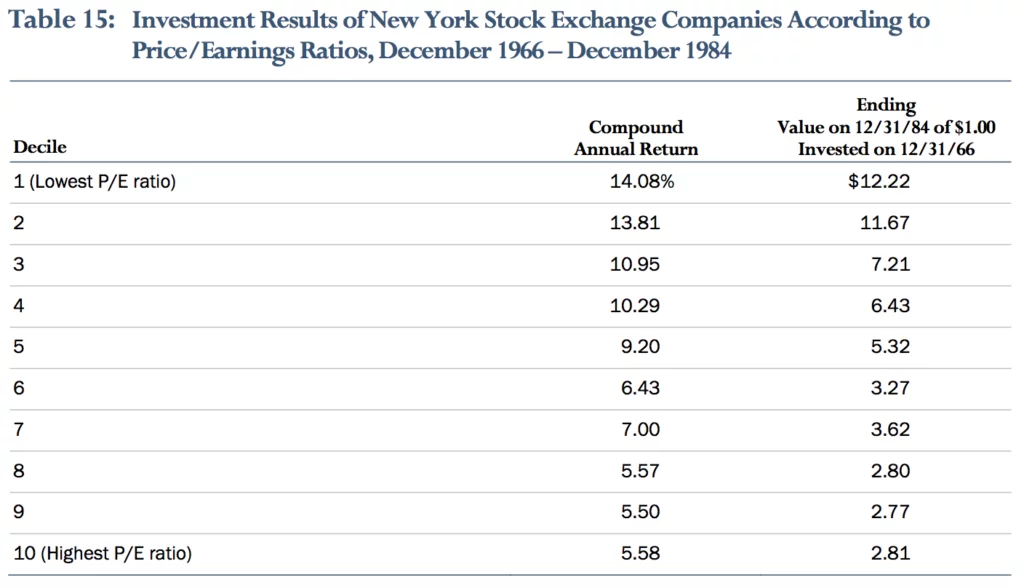

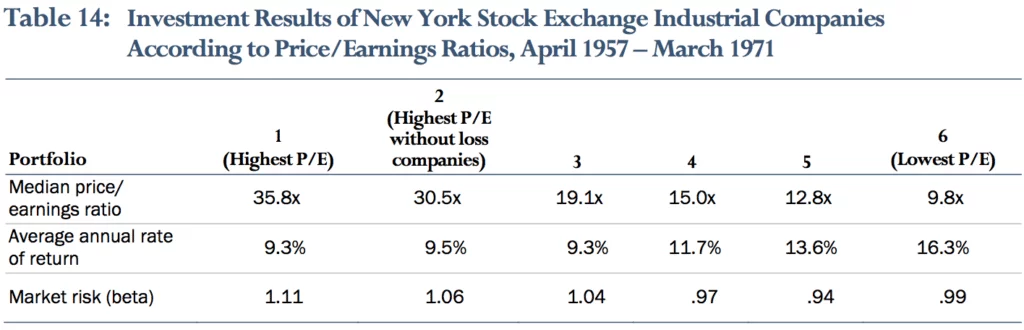

Tweedy, Browne came out with a wonderful investment guide titled, "What Has Worked In Investing," which highlights just how powerful deep value investing strategies are within the context of classic value. Here's one table that looks at low price to earnings companies:

The power of deep value should come clear looking at the above table. All deciles from 1 to 5 can be considered classic Graham value stocks. Taking the 5th decile as the market's central tendency, Firms trading in the 1st and 2nd deciles see a massive boost in returns. Graham also capitalized on these ridiculously cheap stocks using his Simple Way strategy.

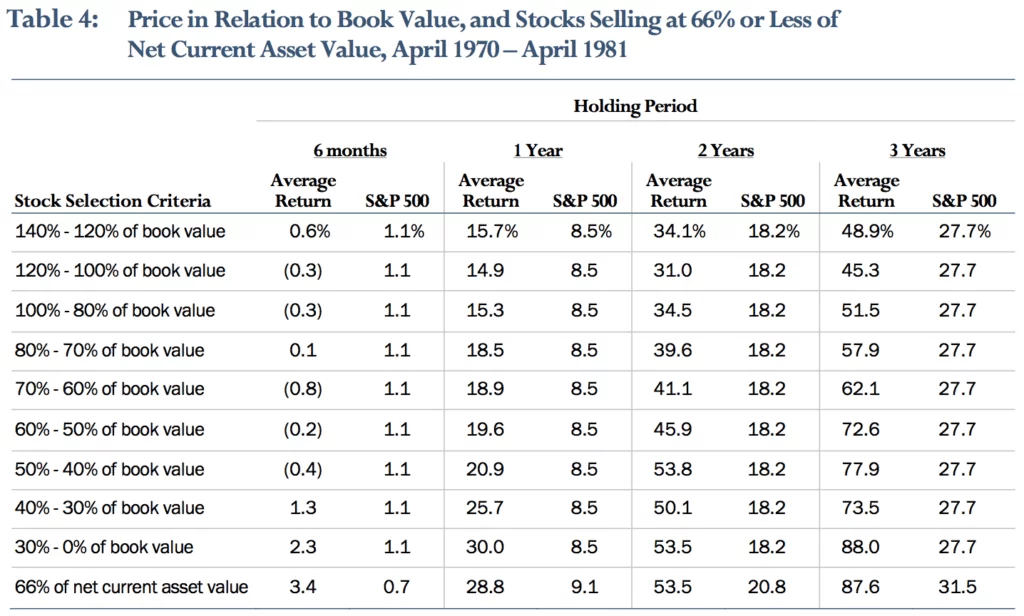

But returns get down-right crazy when we start moving into much more conservative assessments of value. For example, take a look at how very cheap prices relative to book value and net current asset value stocks perform in this table here:

As you can see in the table above, firms trading for small fractions of their book value do very well… but net current asset value stocks, or net nets, trading at a much shallower 1/3rd discount perform just as well. In fact, net nets investing is my favourite investment strategy which is why I've put together a thriving community of deep value investors who focus on net net stock investing.

Is Deep Value Investing Risky?

The irony is that while most of these firms are suffering large business problems, deep value stocks are fairly low risk as a group. Depressed firms suffer smaller drops than high flying companies when bad news hits. Many deep value strategies can even ride-out some market downturns, providing a solid gain for your portfolio during a down year for the index. This is why Jeremy Grantham wants you to stop looking at yield curves and just buy deep value. Market drops also tend to be smaller on average, and recoveries from those drops much more rapid.

So, on all counts, and based on the performance of my own real world portfolio, deep value investing is less risky than buying just about any other sort of value stocks.

Final Thoughts On Deep Value Investing

It's pretty obvious that deep value is the obvious choice for small investors today. The returns are excellent and you don't have to have Warren Buffett's investment genius in order to reap the rewards.

But keep in mind that buying deep value stocks is not like buying high quality businesses - it requires a significant amount of diversification. It also requires the ability to sort firms with solid value from firms that are just junk. All of this requires some degree of investment skill, even if it's not on the level of the Oracle of Omaha.